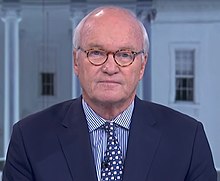

Mike Barnicle

Mike Barnicle | |

|---|---|

Mike Barnicle in 2018. | |

| Born | October 13, 1943[1] Worcester, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Boston University (1965) |

| Occupation(s) | Journalist, commentator |

| Years active | 1965–present |

| Spouse | Anne Finucane |

| Website | mikebarnicle |

Michael Barnicle (born October 13, 1943)[1] is an American print and broadcast journalist, and a social and political commentator. He is a senior contributor and the veteran columnist on MSNBC's Morning Joe. He is also seen on NBC's Today Show with news/feature segments. He has been a regular contributor to the local Boston television news magazine, Chronicle on WCVB-TV, since 1986. Barnicle has also appeared on PBS's Charlie Rose, the PBS NewsHour, CBS's 60 Minutes, MSNBC's Hardball with Chris Matthews, ESPN, and HBO sports programming.

Several of Barnicle's columns are featured in the anthologies published by Abrams Books: Deadline Artists: America's Greatest Newspaper Columns and Deadline Artists—Scandals, Tragedies and Triumphs: More of America's Greatest Newspaper Columns with the description: "Barnicle is to Boston what Royko was to Chicago and Breslin is to New York—an authentic voice who comes to symbolize a great city. Almost a generation younger than Breslin & Co., Barnicle also serves as the keeper of the flame of the reported column."[2] Barnicle is also interviewed in the HBO documentary Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists as well as many documentaries on baseball.

Barnicle, a Massachusetts native, has written more than 4,000 columns[3] collectively for the New York Daily News (1999–2005), Boston Herald (2004–2005 and occasionally contributing from 2006 to 2010), and The Boston Globe, where he rose to prominence with columns about Boston's working and middle classes. He also has written articles and commentary for Time magazine, Newsweek, The Huffington Post, The Daily Beast, ESPN Magazine, and Esquire, among others.

In a 2022 Editor & Publisher feature article, "the legendary journalist and columnist" warned of the ‘destruction of democracy’ and talked about the plight and promise of newspapers. He mourned the “disappearance of local newspapers”, suggesting that even though most states have at least one or two major metro papers, large swaths of the nation are without a reliable source of local news, and voiced his concern about the treasure trove of talent the industry has lost in recent years and all the institutional and community knowledge that left with them.[4]

Early career[edit]

Barnicle was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, grew up in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, and graduated from Boston University in 1965. Barnicle worked as a volunteer for the Robert F. Kennedy 1968 presidential campaign in various states. After Kennedy's assassination, Barnicle attended the Requiem Mass for Kennedy at St. Patrick's Cathedral and later rode on the 21 car funeral train to Arlington National Cemetery.[5] He worked as a speechwriter on the U.S. Senate campaign of John V. Tunney and for Sen. Ed Muskie, when Muskie announced his intention to run in the Democratic Party presidential primaries. Barnicle appeared in a small part in the Robert Redford film The Candidate. While visiting Redford's "Sundance" home in Utah, Barnicle was asked to write a column. As reported by the New York Times, the Globe's political writer, Robert L. Healy, and Jack Driscoll, the editor of The Evening Globe, recruited Mr. Barnicle to write a column. He continued to write columns for The Evening Globe, then the Boston Globe, until 1998.[6]

The paper and its columnist won praise with their coverage of the political and social upheaval that roiled Boston after the city instituted a mandatory, court-ordered school desegregation plan in the mid-1970s. In his Pulitzer Prize–winning book Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families (1986), J. Anthony Lukas wrote that Barnicle gave voice to the Boston residents who had been angered by the policy. Lukas singled out Barnicle's column ("Busing Puts Burden on Working Class, Black and White" published in The Boston Globe, October 15, 1974) and interview with Harvard psychiatrist and author Robert Coles as one of the defining moments in the coverage that helped earn the paper the 1975 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service.[7]

Over the next three decades, Barnicle became a prominent voice in New England. His columns mixed pointed criticism of government and bureaucratic failure with personal stories that exemplified people's everyday struggles to make a living and raise a family. Tapping into a rich knowledge of local and national politics, Barnicle had unique takes on the ups and downs of figures including Sen. Ted Kennedy, Sen. John Kerry, and longtime Congressional Speaker of the House Thomas Tip O'Neill, as well as Boston mayors Kevin White, Ray Flynn, and Tom Menino. In subsequent years, Barnicle's coverage expanded as he reported from Northern Ireland on the conflict and resolution there to the beaches of Normandy, from where he wrote about the commemorations of World War II veterans.[8]

Barnicle has won local and national awards for both his print and broadcast work, in addition to contributing to the Boston Globe's submission and award of the 1974 Pulitzer Prize for public service, he received recognition for his individual contributions. Additionally he's received awards and honors from the Associated Press (1984), United Press International (1978, 1982, 1984, 1989), National Headliners (1982), and duPont-Columbia University (1991–92), and most recently the Pete Hamill Award for Journalistic Excellence from the Glucksman Ireland House at New York University (2022).[1]. He holds honorary degrees from the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Colby College.[9][10]

Boston Globe controversy[edit]

In 1998, Barnicle resigned from The Boston Globe due to controversy over two columns, written three years apart. The first column of more than 80 lines of humorous observations had "a series of one-liners that had been lifted from... George Carlin's best-selling 1997 book, Brain Droppings."[11] The paper's editor, Matthew Storin, asked Barnicle to resign "after learning that Barnicle, who claimed never to have read Carlin's book, had held it in his hand and recommended it on Boston's WCVB-TV in June."[11] Barnicle initially refused to resign but agreed on August 20.[12] In 1999, Carlin commented to the National Press Club: "Someone changed each of the jokes just enough, they thought, to disguise them – that part didn't work – and what they did was make them all worse. ... As an example, one of them was just an observation where I said: "Someday I'd like to see the Pope come out on that balcony and give the football scores." And they changed it to baseball! Which is not as funny! For whatever reason, ..."football" is funnier than "baseball" in that sentence."[13]

Barnicle's resignation spurred reanalysis of his reporting on the 1989 murder of Carol Stuart.[14] He had reported that Prudential Financial had issued a check for $480,000 as the life insurance payout for his wife's policy, offering a potential motive for her husband's decision to kill her. However, The New York Times later confirmed that Carol Stuart did not have an insurance policy with Prudential.[15] He came under criticism in the 2023 documentary about the case, Murder in Boston, for his reporting on Willie Bennett, the ultimately innocent man who was accused of the crime. The Boston Globe published Bennett's grade school report cards, his IQ and referred to Bennett as a "mental defective." After the release of the documentary, the Globe distanced itself from Barnicle's reporting on the case.[16]

The Boston Phoenix published an article on August 20 reporting that Barnicle had plagiarized journalist A. J. Leibling in a previous article,[17] and the magazine Boston "began a 'Barnicle Watch' in the early 1990s to try to track down other dubious Barnicle sources."[12] A subsequent review identified a column from October 8, 1995, which recounted the story of two sets of parents with cancer-stricken children. When one of the children died, the parents of the other child, who had begun to recover, sent the dead child's parents a check for $10,000. When The Boston Globe could not locate the people who had not been publicly identified because they had died as well, Barnicle continued to insist the story was true but obtained indirectly from a nurse. Mrs. Patricia Shairs later contacted The Boston Globe to indicate that the story Barnicle wrote was about her family, although she said some of the facts were incorrect. The article states that "[...]there are more differences between the column and Shairs's story than similarities".[18]

Post-Globe career[edit]

Six months after his resignation from the Globe, the New York Daily News recruited Barnicle to write for them, and later the Boston Herald.[19] Barnicle told reporters that he had nothing but "fond feelings for 25 years at the Globe".[19] Barnicle hosted a radio show three times a week called Barnicle's View.[citation needed]

Barnicle has since become a staple on MSNBC,[20] including on Morning Joe as well as on specials on breaking news topics and presidential elections. Barnicle interviewed all of the candidates in the 2016 presidential race.[21] He interviewed the 2020 presidential candidates through his work on Morning Joe.[22]

Barnicle is a devoted baseball fan and was interviewed in Ken Burns's film Baseball in The Tenth Inning movie, where he mostly commented on the 2003–2004 Boston Red Sox.[23] He has also been featured in TV documentaries and programs, including Fabulous Fenway: America's Legendary Ballpark (2000); City of Champions: The Best of Boston Sports (2005); ESPN 25: Who's #1 (2005); Reverse of the Curse of the Bambino (2004); The Curse of the Bambino (2003); ESPN Sports Century (2000); Baseball (1994); and in the TV series Prime 9 (2010–2011) for MLB Network.

Barnicle has received many honors for his work, including the Pete Hamill Award for Journalistic Excellence from the Glucksman Ireland House at New York University.[2]

Personal life[edit]

Barnicle is married to the former vice chair of Bank of America, Anne Finucane;[24] the couple has adult children and lives in Lincoln, Massachusetts.

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ a b "Mike Barnicle". Facebook. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ Avlon, John; Angelo, Jesse; Louis, Errol (21 November 2012). Deadline Artists—Scandals, Tragedies & Triumphs: More of America's Greatest Newspaper Columns. ISBN 9781468304039. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Boston columnist quits amid new allegations Barnicle had beaten earlier call to resign", The Baltimore Sun, August 20, 1998

- ^ Mike Barnicle warns of the ‘destruction of democracy’

- ^ Barnicle, Mike (2018-06-05). "What I Saw on RFK's Funeral Train 50 Years Ago Today". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- ^ Barringer, Felicity (1998-08-17). "Furor Over Globe Columnist Exposes Fault Lines in Boston". The New York Times. Retrieved 2022-06-04.

- ^ Pulitzer Prize Website

- ^ Amid the graves, gratitude lives on, The Boston Globe, June 7, 1994

- ^ "Around the Pond Summer 1997". www.umass.edu. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ "Colby College, 1987 Commencement". Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ a b Kurtz, Howard (1998-08-06). "BOSTON GLOBE'S MIKE BARNICLE TOLD TO RESIGN". Retrieved 2019-04-26.

- ^ a b "Boston Globe Columnist Barnicle Resigns Over Fabrication Questions". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 2019-04-26.

- ^ George Carlin, Larry M. Lipman (1999-05-13). Brain Droppings (television production). Washington, D.C.: C-SPAN. Event occurs at 40:14. Retrieved 2019-04-26.

- ^ Barringer, Felicity (7 August 1999). "Standoff Between Boston Globe and Its Star Columnist Provokes Turmoil in Newsroom". The New York Times. Section A, Page 14. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ Butterfield, Fox; Hays, Constance L. (January 15, 1990). "Motive Remains a Mystery In Deaths That Haunt a City". The New York Times. Section A, Page 1. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ Walker, Adrian (December 11, 2023). "Years later, a look at the media's sins in the Stuart case". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Dan Kennedy (1998-08-20). "Striking Similarities Mike Barnicle, this is A.J. Liebling. Have you met?". The Boston Phoenix. Archived from the original on 2017-03-21. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ Rodriguez, Cindy (26 August 1998). "Column Had Similarities to Couple's Story". The Boston Globe. p. 27. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Barnicle signs on as Herald columnist". The Boston Globe. Accessed 12 July 2007.

- ^ "Mike Barnicle". MSNBC. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ "Mike Barnicle on 2016". www.mikebarnicleon2016.com. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ "Mike Barnicle on 2020". www.mikebarnicleon2020.com. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ Video, The Tenth Inning, PBS

- ^ Ferro, Shane (2016-01-21). "Banking Doesn't Have To Be A Boys' Club, Bank Of America Exec Says". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- Heslam, J. (November 30, 2007). "Barnicle back on WTKK". Retrieved October 6, 2014.